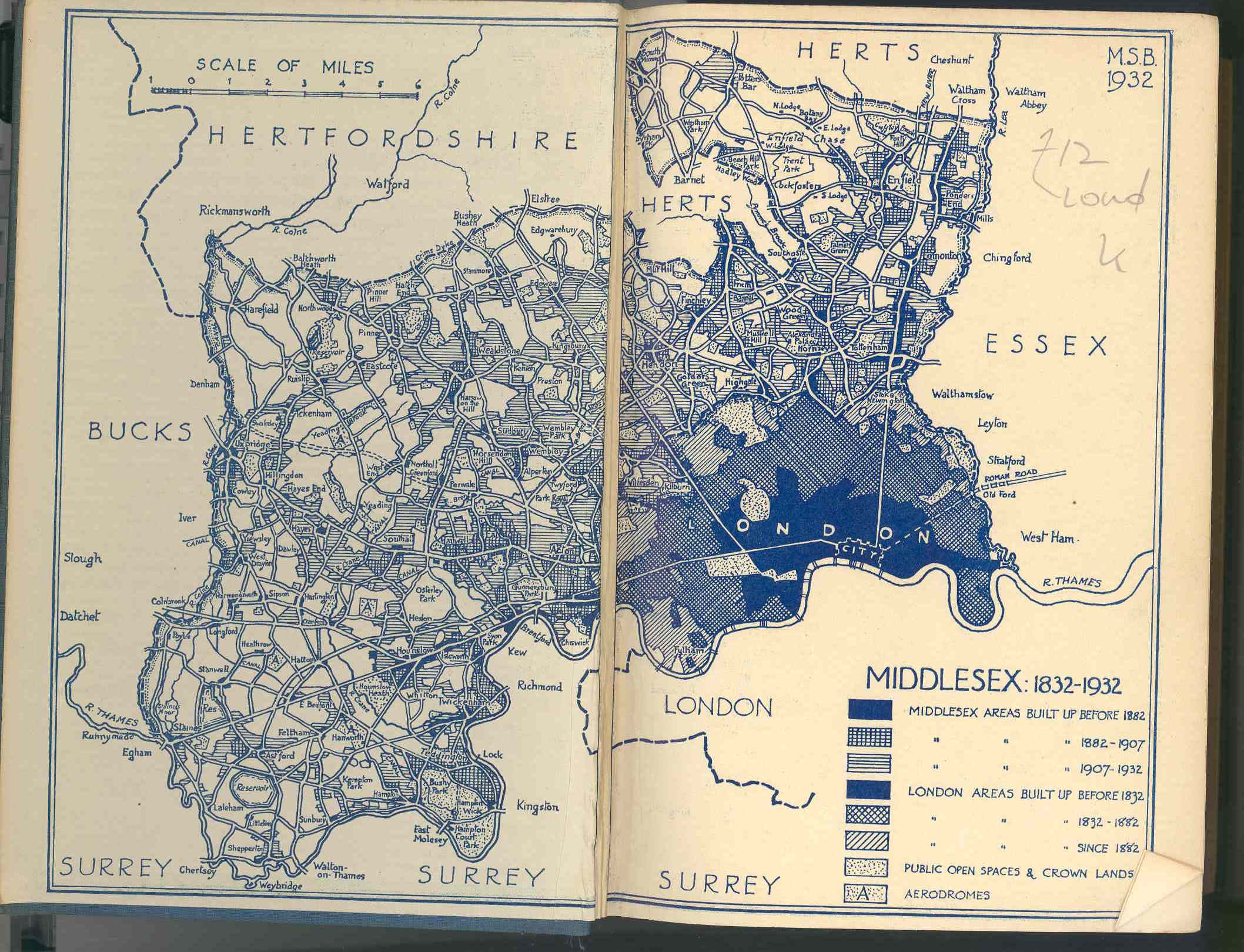

Middlesex in 1934. From Middlesex Old and New

by Martin S Briggs

There are many that maintain Middlesex no longer exists. A bookseller in Hampstead enjoys sneering at my interests whenever I purchase books on the subject. Others come out with the wearying “Middlesex? That’s just a set of postcodes for people who don’t want to admit they live in London.” To be sure, the redefining of London’s administrative districts in 1964-5 supposedly did away with the County civil parishes and Rural or Urban District Councils. In their place emerged a motley group of London Boroughs, each of them inward facing and administratively isolated from its neighbours.

Yet the resonance of Middlesex lingers: Walk down the Hendon Way, from Child’s Hill to where traces of old UDC sewage farms are still visible in the concrete culverts, the raised line of the buried aqueducts at Brent Cross. Work up from there to Hendon, to Sunny Hill Park (noting the old Hendon Corporation metals set into the alleyways and road surfaces) and gaze over to the line of ridges running east to west along the old county borders. Allow the eye to roll far off, across the landscape beyond Harrow, to Haste Hill at Ruislip and to windy Harefield on the western border of the County. Next, cut through to Mill Hill via Arendene open space. Looking west again you see the hills at Red Hill, Barn Hill and Harrow (elongated ridges from this perspective) looking like dreadnoughts in line-abreast. Behind twinkle the lights of distant arterial roads and the tower blocks at Hounslow Heath.

At moments like this the County sits in the palm of my hand or it hangs suspended in the cortex. At other times it is a wild vicious thing: squashed insects on summer bitumen; dead souls trapped in pre-stressed concrete; sadness floating across wind-hacked sportsfields on lonely winter rambles. The county is both an intimate friend and a threat. It is the sparkle of sunlight on red suburban rooftops on spring mornings. It is compressed decades of endless car journeys down the A406 North Circular - drivers languidly farting in their Ford Capris.

Here are some other things the County has stored in its regional memory banks:

-

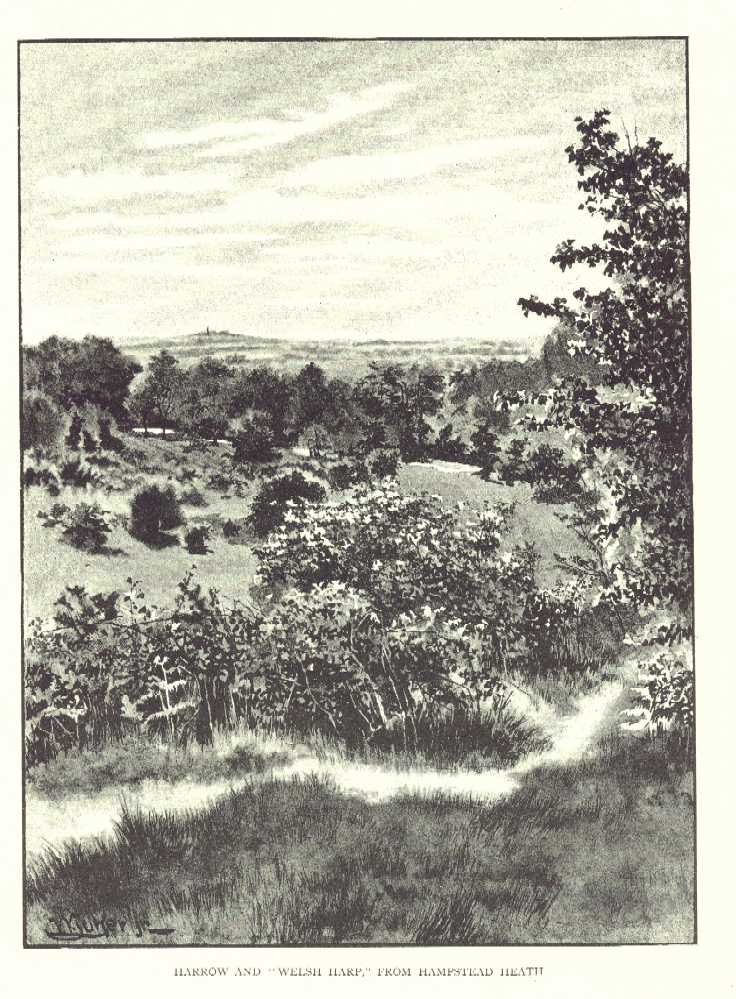

The sighting of a UFO over Harrow by two policemen in 1983.

-

The so-called Black Beast of Enfield, a large wildcat said to frequent the Chase.

-

Gradients supporting the surfaces of suburban streets. An eye for these will throw the topography of the county into stark relief (and undercut the purely symbolic relation with the suburbs that dismisses them as boring).

-

Regional recall in names of streets and schools (Spout Lane North at West Bedfont, Oliver Goldsmith school in Kingsbury).

-

There are traces of old hedgerow in many places – along the Waterfall Road between Friern Barnet and Southgate for instance.

-

The giant Minchenden Oak growing in a dedicated garden in Southgate.

-

Lingering shockwaves of the war stored in concrete slabs, tarmac and pub myths (My newly discovered Aunt telling me about the flying-bomb incident at Standard Telephones & Cables in 1944. How she and her sister stood outside on Bounds Green Road waiting for my Grandmother to come out. When she finally emerged she was white with dust and totally deaf).

-

Buried memories of forgotten disasters (The Brent Cross Crane Disaster of 1964).

-

Elements of county recall in the poetry of Bill Griffith or John Betjamen.

In coming months I will be building up a composite picture of the region. I will also undertake a partial study of neighbouring counties. A series of chapbook publications is planned and will be made available for download or for purchase in hard copy (the first of these, Cul-de-sac, is almost ready now). Please revisit the site periodically and track changes and improvements.

The County lives within us!

One day, about a year ago, I was travelling by bus along the A41 Hendon Way when I happened to look down at a signpost in the front garden of one of the houses on the road’s western side.

It was the sight of the sign – ornate, clearly not “official” - that initially drew me, but it was the sign’s very wording that held me and got me thinking. For within feet of the endlessly dense traffic grinding along this slick black giant of civil engineering worming out towards Edgware and Watford, was the unlikeliest pointer to some understorey of possibilities and worlds:

This rustic sign straight out of a world of small lanes, bowhereens and pubs placed in front parlours read –

TOBAR MHUIRE

OUR LADY’S WELL

Neither was it the clearly Irish origin of the sign that prompted me to ponder, pulling me out of my dull-eyed early-morning trance; after all it was easy to comprehend that it was a talisman brought over from somewhere on the Emerald Isle as a keepsake. Rather it was the sign’s reference to a well that grabbed me. For, upon reading the words inscribed I returned to my on-off speculations about the various courses, the seeping and burrowing, and the flooding, the engineered accommodation of the old streams, ditches and rivers of my region.

Where Riverrun Barnet begins...

To be precise, I looked round me and wondered if there wasn’t a well thereabouts, perhaps in the house’s back garden. A well, or a waterway rendering the sign more than purely decorative. And you know, there was…

The land drops down steeply from behind the house, descending across the artificial plain of the old Hendon Aerodrome (now the Grahame Park Estate) towards the Silk Stream, that close-runner to the claim of London Borough of Barnet’s premier waterway. Shorter, narrower, perhaps in some ways prettier than the Dollis, the Silkstream could be seen as the little sister of the pair. Across the A41 towered the mass of Hendon, Sunny Hill Park with its views westwards and what I call the Sunningfields promontory, a sandy spur covered over with roads containing some of Hendon’s earliest “quality” suburban villas (such as Sunningfields Road, hence the name). Was there a stream perhaps issuing from somewhere off this high ground and running downhill, under the main road and through the grounds of the house?

That evening I consulted my collection of old maps and found there was a tributary of the Silkstream close by the house’s location. I went out to read the land a week or so later.

Sunnyhill Park provides extensive views to the west, over to Harrow-on-the-Hill, Haste Hill near Ruislip and the chalkdowns at Harefield, on Middlesex’s margin. The railway north, M1 Motorway and, of course, the A41 all gently curve below, towards their respective gaps or tunnels in the South Herts tertiary escarpment a few miles away. In the 1920s and 30s crowds assembled here to watch the air pageants held on the aerodrome below. It was a likely spot for streams though their precise course is difficult to discern. Working north along the parks highest point from Hendon church one sees several likely gullies, occasional damp stains running down into the valley. These often align with gaps in the houses clustered below. Further on a line of old hedgerow descends the hill, a small rill hidden in its base. I will not itemise all of these courses just yet as it is with the specific prompt, the stream that initiated all this exploration that I am concerned right now.

It is towards the north of the park, after the high path drops down to an intersecting track leading to sports huts and a teashop, that a damp stain can be seen running along the grass’s lowest point. Aligned with this dampness are a set of manhole covers and curious undulations in the ground surface suggestive of a riverbank. The watercourse comes down off the high ground to the east, off the Sunningfields promontory. In fact; it heads in the direction of the park gates and the A41, probably taking additional waters off the long drainage ditch running along a large part of the park’s western edge, where this backs up against the gardens of the houses just there.

A look at the 1822 OS map of the area shows a small stream running down to join the Silkstream from the high ground of Hendon via a gully. Further, the exit to the park, through which the possible stream ran, was more or less opposite the Irish direction sign. Actually the stream does run here – though I know longer recall how I verified this as the relevant notebook was lost last year, left in a telephone box in Camden Town. After leaving the park it turns north before crossing beneath the A41 and curving back south.

I crossed the main road via the subway there and turned a little up Wheatley Close, where some new brown-brick houses had been built. Looking over the fence of a house I saw my stream. It was running along behind the houses in the general direction of the home with the Irish street sign. So I was correct: the sign was more than merely decorative; rather, it was placed to honour these wellsprings and echoes that underlie our turbulent everyday madness. I was also aware that in following my hunch, in being attentive to the screened-out land and its shapes. I had linked up with a kind of older mind, a mental correlate to the planet’s forces buried deep within the cortex. There was a sense – to be duplicated again and again, of linking up with the past, or with processes operating at a different magnitude to the snap-shot of a million-year process that we take as “reality.”

Which version of reality exactly...?

The "Alleyway Brook" heads for the A41

I found upon further investigation that “my” stream actually ran to the south of the old aerodrome, crossing Aerodrome Road and passing through the grounds of the Peel Centre. It is visible as a slight elongated undulation in the surface of the Police College’s sportsfield.

The stream eventually flows under the underground railway, across a fragment of woodland, under Colindeep Lane and into the Silkstream through a concrete-sided outlet in Rushgrove Park. For the huge bulk of its course it is buried below ground. I call this stream the Sunningfield Brook for no other reason than that I sense it rises somewhere close to the street with that name.

I was pleased at what I had found, at the verification that I had some ability, however slender, in the field of topography.

This is how this website, Riverrun Barnet began. A week or so later I started a three-month course in web-design, part of a back-to-work initiative funded by the European Council. I decided to build this site as my course-project and spent the next few months closely scrutinising old maps, walking miles across the Borough, consulting geological text-books and taking photographs – all on top of the demands of the actual course itself. I received a few odd looks from my fellow students and I’m not sure the organisation running the course had ever had a student produce this sort of thing but, of course, aren’t we proud when we confound expectations, even while we make noises about “narrow-mindedness” and so on. Overall though I had nothing but support.

Shortly after I found a second tributary of the Silkstream, this having its confluence close to but shortly north of the first. I traced it on old maps and where it surfaces, on a current 1/25000th OS. According to the 1822 OS as duplicated in the excellent Village London Atlas (Village Press 1986) this stream rises somewhere up close to Copt Hall or Page Street. I believe it is the little murky rill running in the hedges adjoining the old M1 feed road alongside Bunns Lane and it comes down through that dense mass of trees and hedges across the A41 Holcombe Hill, Mill Hill. Somewhere it disappears beneath the Grahame Park Estate and is discernible in a low-point on the western end of Aerodrome Road close by it joins Colindale Avenue.

A train journey to Burnt Oak and back provided me with a glimpse of the glittering brook weaving through shrubs off Colindeep Lane and shortly after I went down to have a look at closer range. Opposite Rushgrove Park I climbed a fence into a dense elongated piece of emergent secondary woodland. Large yellow elders, coppiced hawthorns and masses of Ramsons and Sauce Alone grew everywhere. I saw Horse chestnuts and some thin tall young oaks also.

The zone of secondary woodland off Colindeep Lane

There was a sense of this peculiar zone being a flood-valve to take waters when the Silkstream was misbehaving. I traced through northwards along tracks probably worn by local kids until I found my stream amidst a sickening malarial thicket of snapped willows and urban detritus. I traced it back as far as where it came through a pipe from under the railway. It was beautiful. The stream has its confluence with the Silkstream behind Chalfont Court, a select group of flats off of Colindeep Lane and so I call the stream the Chalfont Brook.

Two views of the "Chalfont Brook." The brook flows through a

pipe under a rough footpath and into the Silkstream

Later I found another stream coming out from behind the mainline railway along the little footpath adjacent to Rowan Drive, the one that leads from Aerodrome Road to Colindeep Lane, bypassing the mouth of the tunnel carrying tube trains beneath the Hendon Massif. I figure that this is a tributary of the Sunningfields Brook and rises somewhere to the west of the Burroughs, Hendon, coming down through that estate of new houses built on land owned by St Joseph’s Convent. It is traceable in a fenced-in green swathe on the eastern side of the A41, opposite where Selborne Gardens rides off from the flank of the grizzled arterial road. My name for this tiny issue of water visible through the masses of vegetation, the stumpy stanchions and stacks of railway rubbish along by the alleyway is the Alleyway Brook but we could, I suppose, call it the St Joseph’s Brook. I prefer the former.

The "Alleyway Brook" appearing from beneath the mainline railway

The Silkstream itself runs north to south through the Borough of Barnet until it empties into. the Brent at the Welsh Harp. As seen on the "Sources" page of this website, the Silkstream has its origins in a series of rills, riverlets, ditches, conduits and hatches rising high above Edgware and in Stanmore and Mill Hill. The Silkstream proper is formed at the point where these numerous watercourses have come together as the Edgware and Dean Brooks and these, in turn conjoin after passing beneath the Deansbrook Road just to the north of the psychiatric block at the Redhill Hospital.

Prior to this confluence the Edgware Brook crosses under the A5 at a very old bridge.

The Silkstream has, on occasion, been a river of tragedy: back in 1909 Frederick Burgess, a labourer from Childs Hill abducted Anne Lydia Fletcher, a small girl aged 5 years, and dumped her body in the brook behind the Bald Faced Stag public house after repeatedly stabbing her. Burgess stood trial and was declared criminally insane.

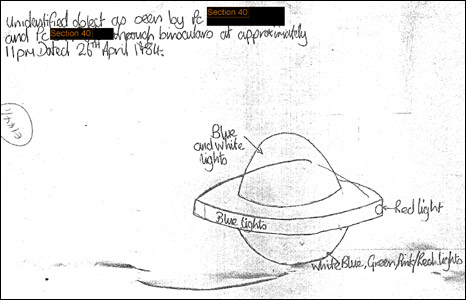

The view towards the Welsh Harp, meeting point of two rivers.

Beyond is Harrow on the Hill

A long footpath runs between Edgware and Burnt Oak alongside the Silkstream and the electric railway. The 1935 6-inch-to-one-mile OS map (Middlesex sheet XI.I.) shows a small feed stream running beneath the railway and footpath and into the Silkstream from the west, from the area of a sports ground. The stream is still there today, visible as a sparkling blackness just opposite where one of the new benches has been placed along the footpath’s length.

Spotting this by chance just recently, when I sat down to have a fag, I traced back up the footpath north, to Deansbrook Road (noting on the way that the chimmney by the Croft has gone) and turned right towards a low-point in the surface ahead. I turned right again into that new estate there, the one with streets named after famous cricketers. At the estate’s south end, where trident pales separate it from another recent development I turned down into the green space at the back of the flats. I was now, by my estimate, directly opposite where I’d seen the stream earlier on the other side of the railway tracks. And there it was, black and sparkly, running out from below a cement-based manhole cover. The water was speckled with fragments of white blossom and disappeared into some vaguely discernible culvert under the railway.

The "Railway" Stream surfaces adjacent to the Northern Line

Where the rill rises I have no idea. There was a suggestion of low ground running straight along the boundary between the two estates, beneath the base of the palings (this is what I call a run), but also another run alongside the railway all the way from Deansbrooks Road to the flats where I saw the brook surface.

Intent on getting to the bottom of this I returned to Deansbrook Road and crossed over (at the roads lowest point thereabouts, remember). Across the way, just west of where Wenlock Road leads off from Deansbrook Road, there is a grassy patch leading through to some new houses. I noted what looked like a dry river course in the grass, curving left towards where the railway cut under the road. There were a few small willows standing there and further on a mass of blackthorn. I rummaged around in the thorns and found a tiny little stream cutting through the undergrowth. It was a thing of rare beauty and I was very pleased to find it and to have my theories verified, my facility demonstrated in this way. I suspect the spring joins the Deansbrook nearby, somewhere by the railway line.

As always I am at a loss to name these little watercourses so I call the first the Railway Stream and the second the Wenlock Brook (though “brook” is perhaps too grand a title for such a diminutive thing!)

The tiny Wenlock Brook found beneath the Deansbrook Road

I lived alongside the Silkstream for a while back in 1971. My family were staying in the Croft, East Road, a homeless families’ hostel run by London Borough of Barnet. East Road at that time was home to a set of derelict factories – now replaced by characterless orange maisonettes – which seemed to catch fire one by one.

The Silkstream ran through burr-fields and ravings of elders and brambles – big black blobs in the late winter – and was inevitably the focus for young members of the Burnt Oak Bootboys. I smoked my first fag down by a rope-swing dangling over a curve in the stream, had my first fumbles with a girl named Maureen Mulling. Timmy Driscoll – later to live at Manor cottages by the A406 in East Finchley – gave me a tasty black eye for…for nothing in fact.

The Silkstream close by Colindeep Lane

Now I walk along this length of the river and much has changed: the tall chimmney that stood at the edge of the General Hospital’s grounds, for instance. The Croft is still there though I am no longer certain which window led through to the small white-painted bedroom I had. My dad and brother are dead, as are many of the Burnt Oak Bootboys; heroin took them in the 1980s. And Maureen? God knows. Those moments we had, of fear or joy, the plimsolls we wore by the mad stream, the two-tone tonics and Harringtons, the Fabs licked and sucked, the fags in long grass – they all rose to eternity, spiralling up into the Middlesex Sky to be stored in some vat of regional consciousness located beyond the Brockley Hills, the distant pylon-plateau of yearning.

It tears the heart, this inability to capture a place, a moment, maybe and store it in one of my old Kilner jars, rendering it retrievable in some more substantial form than mere memory and word. For I would present it to you and you would accept it with the love intended. And together we would walk into this landscape once again, restored to youth and hope.

The Silkstream enters the tunnel beneath Watling Avenue

Both the Burnt Oak Brook and the Silkstream flow through the Watling Estate, one of the old London County Council cottage estates built in the late 1920s to absorb population overspill resulting from slum clearance in the East End. I recall Watling back in the 1970s, the mixture of toughness and pride, the close-nit family networks, the criminality and decency intermingled. There were Hopcrofts’ and Burshalls’; a girl named Wendy Tapping everybody fancied; a mythic character a few years older than us named Stephan Werth who was reckoned to be well-hard.

The Silkstream runs under Watling Avenue via a tunnel mouth situated below backs of shops and adjacent to the Watling Market. There is something forbidding about this gaping maw of the tunnel, topped by an oxide-coated steel beam. The stream runs beneath the lives, below the stridency of this synthetic town with its pigeon fanciers, given over these last twenty years to fat coffin-like cars and sealed windows. The stream flows into darkness for a mere moment, dreaming no doubt of Death’s mouldy tits. The stream passes into memories of the Watling estate but these are nothing more than the dream of a mushroom god, having their moment and then gone!

I recall back in about 1971 looking down the stairwell leading from street level to the area designated for use as a market. Dozens of young men – aged about 13 to 15 – were bouncing up and down on the curved sheet-metal roofs of the market stalls, throwing pieces of tubing at each other. One of them lit a cigarette and glared at me, turning to speak to a pal who looked my way too. I didn’t recognise any of them as from my school, Goldbeaters, and feared they were Orange Hill Boys. I made myself scarce, preferring to get home by ascending Watling Street to Burnt Oak Broadway, walking past the cinema and the Wimpy Bar and down North Road.

The market was born of local belligerency: an article in the Hendon Times from boxing day 1930 and headed ‘A Watling “Riot”’ tells of how the Edgware police were pelted by a hostile crowd after attempting to close down an illegal market stall. Poor sub-divisional inspector Paice attempted to enforce a court order forbidding the busy pavement trading that was forcing the people of Burnt Oak to walk in the road. In particular he had it in for one Edwin John Powell, 24, 0f 80 Littlefield Road and Henry Thomas Whytock, 21, of 175 Pembroke Place, Edgware. Paice ordered Powell and Whytock to move their stalls whereupon Powell answered “I am only trying to make a living. Do you want me to go on the dole.” Paice ordered his colleague, Sergeant Clarke to take matters into hand and Powell kicked the good sergeant in the leg. Whytock then punched Paice “hard enough to daze him” and the crowd, reported as 400 strong, pelted the police with apples, oranges and onions.

The whole problem arose from the fact that the Watling Estate was badly served by shops in the first few years of its existence. Locals had to go to Edgware or Colindale to buy supplies and the coster-barrows were merely filling a local gap in the market, providing a service to the displaced Londoners relocated in Topham-Forrest’s LCC dream-town. It was in order to cover this need that an area was eventually dedicated as a market and continues to serve the local community down near the banks of the Silkstream.

It is worth noting here the many old trees dotting this remarkably beautiful estate, some of them relics of the area''s rural past.

On the far side of Watling Street the Silkstream is joined by the Burnt Oak Brook at a confluence tangled with tipped willows and ravings of summer bindweed. All through Silkstream Park the river is strewn with shopping trolleys and slime and then passes into Montrose Sports Field.

The brimbling brook running through bucolic Silkstream Park

A report in The Times dated December 13th 1922 stated that the Silkstream would have to be diverted to accommodate the new tube railway linking Hendon with Colindale, Burnt Oak (Watling) and Edgware. It was anticipated that 12000 tons of soil would be removed in this work. A stream feeds the Silkstream on the Montrose playing fields close by the old tram shed that served the Hendon Aerodrome railway, with a second feeder having its confluence directly opposite, by Merit House on the A5, this latter rising in Kingsbury. These two streams have been described collectively as the Tramway Ditch.An aerial photograph taken in 1922 and included in David Sullivan’s book, The Westminster Corridor (Historical Publications, 1994) shows extensive flooding of the Silkstream on either side of Watling Street. Following this the land was channelled between concrete embankments. At one point a canal company managed this stretch of the river! It is worth noting here that Mr Sullivan''s book contains a map ("Map N") that indicates the brook I call the Chalfont Brook formed part of the boundary between the pre-Norman "tracts" of Lotheresleage and Heandune.

Looking across the valley of the Silkstream

from Sunnyhill Park

Rivers, Rills, Streams and Hatches, Cesspool Overflows and Drainage Ditches of the London Borough of Barnet

A wet Tuesday morning in April: a shiny hearse, followed by a motorcade of battered family motors, turns decisively through the gatehouse of the Hendon Cemetery. As a life is laid to rest in the sopping clay a dirty-faced boy of about six screams at his mum, warning her not to wipe the snot, the grease from cheese and onion crisps and the tears from his face.

A few car-journeys along the A41(T) and they''ll be laying our boy out too. The skies will wheel, seagulls cry down the long dusky avenue of the years. Our current obsessions will sink into the past and be off no interest to anybody. I too will depart, taking with me my peculiar myopic intensity, my spiteful fancies.

As the coffin is lowered into the hissing ground a deeper note intrudes. Deep-set within the herbage, where lines of trees and hedges meet, two gurgling streams, travelling down from the Mill Hill massif, combine and head off on a journey to Brentford and the Thames.

Follow them through, alongside a garden and under the road to their confluence with the Dollis Brook behind the parade of shops opposite the cemetery. Shoppers pass here, on Holders Hill Road. They are indifferent equally to the death-wrapped mouners and the life of the streams flowing beneath their feet. And that is how it is, isn''t it? This elemental processing of life and geology taking place where we wait for buses, carry French sticks and soup home for Eastenders and SkySport.

The Author surveys the wreckage...

Further up Holders Hill Road, the Great North Way slices through ancient Ashley Lane and rises to views of St Judes Church over on the Hampstead Garden Suburb. That quiet dead-end street, Garrick Gardens, ends at a six-foot fence propped on a retaining wall. On the other side the ground level rises in a terrace. A century ago there was a waterfall here. A rillet rising on the Sunnyhill promontory to the west had its force harnessed for the benefit of the owners of Hendon Hall, nearby.

By the time the 1966 England World Cup Squad gorged on scampi and quaffed their wine at the Hendon Hall Hotel, waiting for the historic final the waterfall had gone, torn out in the spirit of utility, pushed aside by Batman, by felt-tip pen. Yet the feed-stream remains, buried and traceable in alignments of alleys and roads, running straight ahead down to the ] Dollis where it pours out a pipe set in the embankment below the ends of back gardens.

In a sense this site is concerned with the hidden worlds. Behind the business of our concerns, our dashing and worry, the rivers, streams, ditches rills and rillets run. Though in no-way an eternal counterpoise to our ephemarality, these waterways persist, operating on a different level of duration to our lives and traceable on the various Ordnance Survey maps produced over the last two centuries.

Three watercourses meet in the Hendon Cemetery. The southern-most flows in from across an adjacent golfcourse having risen on Arandean Hill, a mile or so to the north. Another rises to the west of the former, possibly picking up waters flowing down the long roadside ditch on Milespit Hill. It is clearly visible below Sanders Lane where that road rises to cross the disused railway that once ran between Mill Hill and Edgware. It runs along Ashley Lane and crosses into the cemetery picking up another stream running down through the site of the old Mill Hill gasworks.

Riverrun has been set up as the first river-survey for my mother-site Middlesexcountycouncil I have decided, for reasons of ease, to focus on the streams and rivers of London Borough of Barnet, where I happen to live. A good few months surveying land forms, scrutinising maps and books and walking have gone into its production. I must state here the debt I hold to Hugh Petrie and Yasmin Webb at the Barnet Borough Archive in Mill Hill, to Pete Knapp, my long suffering and frequently terrified photographer, and to all those others who put up with my flights of fancy, visions and rants.

A stream flows through West Heath, Hampstead.

Later it will become the Clitterhouse Ditch, joining the Brent

opposite the Regional Shopping Centre

There are two basic types of text contained on this site: Factual detail of the course of the rivers prefaces each page. Where they rise, their history and descriptions of the land they move through. Interwoven with these objective particularities is a more subjective type of account, an attempt to sink down to the underbelly of the streams'' being through imagination and emotion. The two approaches often intermingle, but a broad distinction will be clear from a difference in font and font-colour.

While researching for this site I often returned home with a sense of having pierced the thin veneer of appearance, of having penetrated to a place where time compresses, many eras becoming manifest at once. I have been driven by a sense of urgency, of duty almost, to communicate what I have seen and experienced yet I suspect there will be scant interest in what I have to say. So much environmental writing nowadays is little more than a faded type of organicist ideology - picnic tables and wheelchair access amidst the native species; either that or yet another foray into the cult of the predictably "quirky" manifest in "psychogeography," "Crypto-topography" and, indeed, "Deep topography."

One must be attentive to detail in the landscape

when tracing rivers and waterways. Hover and click

to see where these plates lead

Some difficulty was experienced regarding a workable definition of what a stream or river actually is. Did I include, say, 18th century drainage ditches in that category? If so than why not surface water conduits laid to serve suburban streets dating from the 1920s. In the end I decided not to be too hard and fast about definitions. The project is as much feeling-based as concerned with specifics. If something grabbed me than in it went! For that reason I will sometimes concern myself with rivers and streams that either once existed and now no longer do so or even with streams that may never have existed.

(c) Riverrun 2004

Welcome to Middlesex County Council part II ??

I wish to honour my home, the old County of Middlesex, utilising prose and poetry, photographs and local history lore.

This website has been set up not only to explore and present the historic legacy of old Middlesex, but also to examine the way in which the county-region still coheres as a distinct entity at the topographic and imaginative levels.

Those of us born towards the end of the 1950s will have seen the last of the county as a formal, administrative entity: I recall doing my O Levels under the auspices of the Middlesex County Council Education Department in the 1970s. One of my abiding memories from childhood is of a steamroller moving along Queens Avenue N3 back in 1965. The words “Middlesex Borough of Finchley” were inscribed along the top edge of the driver’s cupola.

Yet despite its ostensive dissolution at the administrative level, the sweep and majesty of Middlesex continues to impinge on the imagination. Answering the call of the county has become the central axis of my written work. Over the last ten years I have built up a sizeable library devoted to all aspects of Middlesex, and intend to make this collection available to the public at some point in the future. Prints and illustrations from the library are viewable in various sections of the website.

I have also undertaken a long series of walks criss-crossing the region in order to defamiliarise my relations with the environment, aiming to throw the county''s landscape, its hills and memories, dreams and imaginings into sharp relief. Some of these studies and explorations are woven into the various sections making up this site.

Many people maintain that Middlesex no longer exists. A bookseller in Hampstead enjoys sneering at my interests whenever I purchase books on the subject. Others come out with the wearying “Middlesex? That’s just a set of postcodes for people who don’t want to admit they live in London.” To be sure, the redefining of London’s administrative districts in 1964-5 supposedly did away with the County''s municipal boroughs. In their place emerged a motley group of London boroughs, each of them inward facing and administratively isolated from its neighbours.

Yet the resonance of Middlesex lingers: walk down the Hendon Way, from Child’s Hill, to where traces of old UDC sewage farms remain visible in the concrete culverts, the raised line of the buried aqueducts at Brent Cross. Work up from there to Hendon, to Sunny Hill Park (noting the old Hendon Corporation metals set into the alleyways and road surfaces) and gaze over to the line of ridges running east to west along the old county borders. Allow the eye to roll far off, across the landscape beyond Harrow, to Haste Hill at Ruislip and to windy Harefield on the western border of the County. Next, cut through to Mill Hill via Arendene open space. Looking west again you see Kingsbury Hill, Barn Hill and Harrow (elongated ridges from this perspective) looking like dreadnoughts in line-abreast. Behind twinkle the lights of distant arterial roads and the tower blocks at Hounslow Heath.

Nick Papadimitriou, Middlesex 2006

At moments like this the County sits in the palm of my hand, or it hangs suspended in the cortex. At other times it is a wild vicious thing: squashed insects on summer bitumen; dead souls trapped in pre-stressed concrete; sadness floating across wind-hacked sportsfields on lonely winter rambles. The county is both an intimate friend and a threat. It is the sparkle of sunlight on red suburban rooftops on spring mornings. It is compressed decades of endless car journeys down the A406 North Circular - drivers farting languidly in their Ford Capris.

Here are some other things the County has stored in its regional memory banks:

-

The sighting of a UFO over Harrow by three policemen in April 1984.

-

Regional recall in names of streets and schools (Spout Lane North at West Bedfont, Oliver Goldsmith school in Kingsbury).

-

There are traces of old hedgerow in many places – along the Waterfall Road between Friern Barnet and Southgate for instance.

-

The giant Minchenden Oak growing in a dedicated garden in Southgate.

-

Lingering shockwaves of the war stored in concrete slabs, tarmac and pub myths (My newly discovered Aunt telling me about the flying-bomb incident at Standard Telephones & Cables in 1944. How she and her sister stood outside on Bounds Green Road waiting for my Grandmother to come out. When she finally emerged she was white with dust and totally deaf).

-

Buried memories of forgotten disasters (The Brent Cross Crane Disaster of 1964).

-

Elements of county recall in the poetry of Bill Griffith or John Betjamen.

-

The ''Crusher'', a large roller causing destruction to buildings in Acton and Finchley in the yeras before the Second World War.

All of these are covered in this site. Dig them out!

In coming months I will be building up a composite picture of the region. I will also undertake a partial study of neighbouring counties. A series of chapbook publications is planned and will be made available for download or for purchase in hard copy (the first of these, Cul-de-sac, is almost ready now). Please revisit the site periodically and track changes and improvements.

The County lives within us!

The Frontispiece of Middlesex Old and New

by Martin S Briggs 1934

It is generally taken that the Dollis is the primary river of the Borough. Following its confluence with Mutton Brook the Dollis “becomes” the Brent, the feeling being that this is simply a renaming of the former stream rather than an acknowledgement of changed circumstances due to two rivers combining.

The Dollis therefore overrules the Silkstream, which is seen very much as a daughter river despite its considerable size and length prior to their confluence at the Welsh Harp. Either way, the Dollis/Brent is the dominant river system of the region. The catchment area for the river totals 67 square miles.

Prior to the formation of Barnet Borough in 1965 the Dollis formed the boundary between Finchley and Hendon boroughs. Towards the end of their roles as effective administrative areas the twin boroughs worked hard to incorporate the river into the greenbelt as a leisure facility. Alfred Pike, mayor of Finchley in 1937/38 and again in 1958/59, recalled the situation in an interview recorded in 1980 and included in Percy Reboul’s book Barnet Voices published in 1999:

The Dollis approaching its confluence with Mutton Brook

(where it will become the river Brent)

One of the things I attach great importance to is the Brookside walk. It starts at Falloden Way, in the Garden Suburb, goes along the brook to Henley’s Corner, crosses over and goes up to the borough boundary. Now I was in Cologne for a conference between the wars and was taken by their town clerk and Burgomaster around the original town walls which had become a public walk with lovely gardens. I thought, why can’t we turn our brook-side into a walk? I worked away at it and Finchley Council agreed to pursue it but when we got as far as Westbury Road where the gardens went right down to the brook, we were bunkered. Our only hope was to see if Hendon would acquire the piece of land on their side so that we had a crossover. I discussed it with my opposite number in Hendon and he thought it a good idea so now we get Westbury Road , cross over into Hendon and go right along to where Lullington Garth starts and then back eventually into Finchley.

However, not everybody was pleased with the way the Council went about fulfilling Pike’s plan; consider the following letter, sent to The Finchley Review in July 1937:

3rd July 1937

Dear Sir, - Only a year ago the area between the gardens of this part of Village Road and the Dollis Brook was as pretty a spot as you could wish to see. The old bed of the stream wandered through a copse of beautiful trees and elsewhere there was a green meadow.

In the summer of last year the Finchley Council acted. Thick logs of trees were thrown into hollows. Lorry after lorry drove up and deposited poor soil mingled with bricks, stones and all sorts of odds and ends.

Soon the meadow had become a desert in dry weather, a mudflat in wet; and in any weather a rubbish dump. Trees and bushes were hewn down to make way for lorries. To the former loads were added others less pleasant, street sweepings, dirty paper and rags, and the cuttings of the local trees.

It took weeks to complete the work of vandalism but at last the Council were content. Gashes had been rent in the bushes, trees and branches had been torn down and over all the pretty spot was spread a hideous desecration of weltering mud and a muddle of brick and stone.

What was the object of this philistine idiocy? If the Borough Surveyor thought to drain the ground, never was a surveyor proved more wrong. The winter rains deprived of their natural drainage via the old bed of the stream, collected in a system of rank pools and lagoons, on the top of which floated the oil risen from the buried road scavengings.

The Council was compelled to dig drainage ways late into the spring.But the full extent of the stupidity is only just revealed. Many of the trees, many of the bushes are dead and many more of both are sickly and dying.

So that the good people of Finchley may enjoy the patch of wantonly destroyed natural beauty, a beneficient Council has scarred the fields with a black asphalt path – Brookside Walk.

And the irony of it all is this: a few days work clearing the outlet of the old bed of the stream into the present Dollis Brook and the winter rains which used to gather in the ditch would have had free egress.

Ah, dear Editor, but I’m forgetting, that would have denied the Council the delight of turning meadow into desert, woodland into a desolation of dead wood and a satisfactorily drained area into a system of evil-smelling lagoons.

Two minor pleasures would also have been denied to the Council. The pleasure of burying wood which might have been firewood for the unemployed, and the pleasure of spending public money on an entirely useless object.

Yours faithfully

Ralph M. Dowson.

12, Village Road, London, N.3.

OS maps of a hundred years ago indicate extensive field drainage systems along the course of the Dollis. While many of these remain (or have become incorporated into surface-water channels beneath suburban streets – see below) the river no longer serves exclusively agricultural interests.

The build-up and suburbanisation of North Middlesex during the 1920s and 30s exacerbated drainage in the area. the hendon and Finchley Times for 7th November 1930 contains the following report:

Consideration has been given by the General Purposes Committee [of the Middlesex County Council] to the application of the Finchley Council for a contribution towards the cost of aquiring two small pieces of land for additions to the Public Walk, which it is intended to run along the banks of the Dollis Brook, the boundary between the Finchley and Hendon urban districts. There is planned a surface water sewer at Wyatt''s Farm, Whetstone, at a cost of £200...the land which is situated on the west of Fursby Avenue and Brent Way was inspected by members of the Committee. The Council agreed to contribute a fourth of the cost.

If you walk along the Dollis between, say, Holders Hill Gardens to Thornfield, you will spot a staggering number of pipes issuing from the embankment above the stream, carrying surface water from nearby streets. Drainage water running off the dense road network in the catchment area of the river has resulted in occasional flash floods. Back in 1968 torrential rains caused several sections of the Dollis/Brent to break its banks, resulting in widespread damage. The GLC subsequently issued a leaflet to homes in the area. The River Brent Valley and You

The Dollis Brook was an abiding presence throughout my childhood. A walk through suburban streets took the family to Ballards Lane, familiar for its shops and bus routes Then along Lovers Walk, between high old walls and over the railway line where train drivers hooted to us. Crossing the busy road at the Lane’s end we came to a lodge house at the top of a tree-lined walk. It was like entering another world. A slope ran downhill with horse chestnuts on either side and a wide ditch to the left backed onto garden fences. A few hundred yards more of tarmac and water and there, ahead, was the brook.

The Dollis Brook was an abiding presence throughout my childhood. A walk through suburban streets took the family to Ballards Lane, familiar for its shops and bus routes Then along Lovers Walk, between high old walls and over the railway line where train drivers hooted to us. Crossing the busy road at the Lane’s end we came to a lodge house at the top of a tree-lined walk. It was like entering another world. A slope ran downhill with horse chestnuts on either side and a wide ditch to the left backed onto garden fences. A few hundred yards more of tarmac and water and there, ahead, was the brook.

I think Lovers Walk probably covers a waterway, presumably the one that emerges by the lodge house on Brent Way and runs down alongside the tarmac track to the Brook at the bottom of the valley. Note there is also a path side ditch running south directly opposite, from somewhere up near Nether Court, the clubhouse for the local golf club. A further stream rising near Nether court flows through the golf course and empties into the Dollis through a concrete-wrapped discharge pipe opposite Brent Way. A look at the 1894 OS map of Finchley reveals that all these ditches were present at that time.

Having reached the brook we would put on wellington boots and play in the shallow water, hopping from gravel bank to gravel bank or plucking dock leaves to salve stings from the nettles which grew everywhere. Sometimes the river was frothy with detergents – quite a common site in those days (see a refernce to this phenomenon in Philip Larkin’s “The Whitsun Weddings”) but thankfully this stopped happening after about 1964. One day we followed along the river from the bridge that usually formed our starting point to the vast hallways of the viaduct carrying trains high over the trees and the rooftops of the houses nearby. I stepped on a piece of wood with a nail in it and it pierced my boot, entering my foot. For months afterwards gently tickling the wound would induce unbearable spasms of delight – my first masochistic impulses.

Having reached the brook we would put on wellington boots and play in the shallow water, hopping from gravel bank to gravel bank or plucking dock leaves to salve stings from the nettles which grew everywhere. Sometimes the river was frothy with detergents – quite a common site in those days (see a refernce to this phenomenon in Philip Larkin’s “The Whitsun Weddings”) but thankfully this stopped happening after about 1964. One day we followed along the river from the bridge that usually formed our starting point to the vast hallways of the viaduct carrying trains high over the trees and the rooftops of the houses nearby. I stepped on a piece of wood with a nail in it and it pierced my boot, entering my foot. For months afterwards gently tickling the wound would induce unbearable spasms of delight – my first masochistic impulses.

There was a fine graffito in large white letters on the base of the railway viaduct: EDUCATE THE USA. The large message, visible to passing drivers pointed to a darker, turbulent world beyond our experience.

In 1972 my younger brother Stavro, my friend Nick Fields and me climbed high through successive brick chambers of the viaduct up to where the trains rumbled overhead. Here we found a used syringe lying in the bare dirt in this sun-occluded place. We phoned the police from a phone box and told them of our find. “OK lads, thanks for the information. Don’t touch the syringe and we’ll send a panda over later to pick it up for fingerprints.” We waited and waited for that panda, standing beneath the trees until the street lights were turning red in the early evening before we went home. 30 years later a similar syringe was to kill my brother.

The Brent and Silkstream meet at the Welsh Harp

There was a small wooden bridge at the bottom of the track running from the lodge house. It is still there but in about 1965 it was joined by an aluminium structure spanning the stream and, presumably, carrying water, gas or some such utility across to the opposite side. I still think of it as the “new" bridge whenever I visit.

On another occasion we went fishing in the lake between the brook and the golf course. We caught dozens of sticklebacks and newts and took them home together with water weeds, placing them in a large blue plastic bath only recently used to bathe my younger brother. I was struck by the sticklebacks swimming around in circles all together and would watch them for hours. I rushed home from school shortly after, eager to see the fish. To my horror they were all dead, their gills white and eyes black and lifeless. The water was yellow and stinking. With a howl of rage I took the plimsoll to my unfortunate brother.

About 1966 we explored further, crossing busy Dollis Road and entering the long narrow strip of parkland running alongside the brook. I remember one day seeing a young man cycle past along the path dressed in a bright red hussar’s jacket!

July 2007: pollution froths the Dollis at Hendon Lane weir

I also recall one hot afternoon in 1968 staring idly at the rundown old tennis huts in the patchy riverside land behind Brent Way. It was the day of the opening ceremony for the Mexico Olympics and I was due home about teatime to watch it on the goggle box, I mention this because it seems so recent, so outside the sequential flow of my life, this event, this staring idly at the decrepit Tennis hut. Rather like the streams and waterways themselves in fact.

The Dollis rises in Barnet Gate Wood, way up near Moat Mount in the north of the Borough. It flows eastwards initially, taking in additional waters from subsidiary streams and from fine roadside ditches along Hendon Wood Lane.

The Dollis eventually curves southwards alongside the long tongue of glacial gravel mounting the Great North Road between Barnet and Finchley Tally Ho Corner. From there the Dollis runs below the Hampstead Heights in a valley far below the Finchley Road. All along the road from Barnet to, say, a little beyond Long Lane, Finchley, the traveller is struck by the fall of land westwards. Around Finchley Central station the view westwards becomes blocked by the wedge of gravels jutting out from the Finchley plateau towards the point where Dollis and Mutton conjoin but, travelling south, one is eventually rewarded with even better views down into the river valley

The best place to see this is by looking down Dunstan Road, just to the south of Golders Green. Extensive views across the valley carry the eye right across to Harrow on the Hill and even further. Deep below the river runs, bearing slightly west as it receives the waters of the Mutton Brook and turning towards its expansion at the Welsh Harp.

A tributary feeds the Dollis, coming off of the gravel beneath the Great North Road at Prickler’s Hill, just adjacent to the old Middlesex and Hertfordshire county boundary. I have never seen this tributary (or not knowingly, anyway. I mean, I have never noticed it) but have read about it in an old Times article dated January 19th 1911:

At Highgate yesterday S Morris, proprietor of the Whelm Laundary, Great-North-Road, Barnet, was summoned for not having complied with two notices issued by the Middlesex County Council calling upon him to discontinue the flow of sewage or other offensive matters into the Dollis Brook, a tributary of the Brent.

It transpired that the unfortunate Mr Morris had missed out on modifications to sewage disposal dating from 1906 when an estate on the east side of the main road had been processed integrated into a local UDC system. Mr Morris’s business was located on the west side of the road and had been overlooked. The defendant decided to take proceedings against the County Council. The sluice is quite likely the one visible on modern 1/25000th OS maps.

As mentioned on this site’s main page, there is another set of tributaries joining the Dollis opposite the Hendon Cemetery.Three watercourses meet in the Cemetery. The southern-most flows in from across an adjacent golfcourse having risen on Arandean Hill, a mile or so to the north. Another rises to the west of the former, possibly picking up waters flowing down the long roadside ditch on Milespit Hill. It is clearly visible below Sanders Lane where that road rises to cross the disused railway that once ran between Mill Hill and Edgware. It runs along Ashley Lane and crosses into the cemetery picking up another stream running down through the site of the old Mill Hill gasworks.

The river is not only a benign relic of the arcadian past or an ideal green utility:the stretch of the Dollis between Hendon Lane and Bell Street was a scene of tragedy back in 1959 when Hubert James Dughard, a 21 year old Indian plastics worker from Muswell Hill strangled a local girl, 19 year old Miriam Young and threw her body in the brook just adjacent to the large watersplash. Dughard subsequently received a life sentence.

Watersplash, dock and long-disused bridge

behind bungalows on the A406

At the junction between the A406 North Circular Road and Brent Street the river drops through a watersplash. There is a pair of curious conical summerhouses, one on each of the river’s banks. These are the final remains of the Brent Bridge Hotel, a once-popular meeting place in the region, which stood on the site of what is now Woodbourne close

.

The sunhouses at Brent Bridge: last remains

of the once-popular Brent Bridge Hotel

Further west, at a point yet undetermined, a small boy, 6-year old John Frederick Petts of 139 Woodstock Avenue drowned while playing in the river back in 1919.

There is a small bridge dating from somewhere around the 1930s still standing on the stretch of the Brent between Brent Street and Brent Cross. The bridge, marked on the 1936 6-inch-to-one-mile OS map is accessible through the garden of a derelict bungalow on the A406. It is at the point corresponding to where Mayfield Gardens forms its junction with Shirehall Park on the river’s north bank. There is also a weir just there and a concrete pier which may be the dock marked on the 1894 map. I went through to visit the bridge in February 2005 and found it covered in ivy. Inscribed in the concrete of the river bank was the inscription “1939 HMG.”

The straight section of the brook to the immediate east of Brent Cross was the site of a further murder in 1921: the body of a woman, Mrs Evelyn Goslett, wife of Arthur Andrew Goslett was found in the brook directly opposite the end of Western Avenue. She had been bludgeoned with a blunt instrument. Police enquiries led to the arrest of her husband who was eventually hanged at Pentonville prison for murder.

(c) Riverrun 2004